Les belles affiches > Special files > Alex Proyas

Alex Proyas: Master of the Image

By ✉ webmaster@lesbellesaffiches.com

Story available in french here

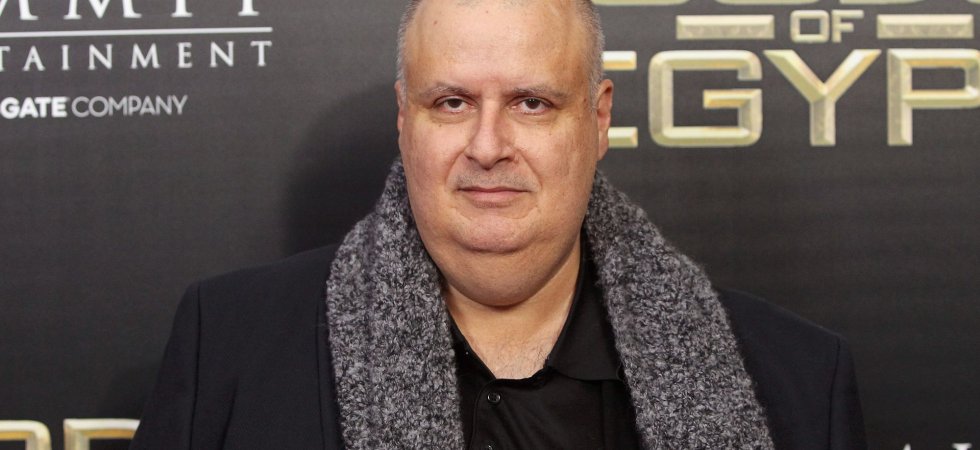

© Cineday Orange

© Cineday Orange

Early days

If there is one man who knows about cultural melting pots, its Alex Proyas. Born in Egypt in September 1963 to Greek parents, he moved to Australia when he was 3. At 17, he enrolled in the Australian Film Television and Radio School. It was there he was to meet and begin working with Jane Campion, a collaboration which would prove more than fruitful. Of his first five short films, Groping (1980) enjoyed the greatest success, both in Australia and the UK. Following these projects, he moved to Los Angeles, where he became a prolific producer of adverts and music videos, working notable for the Propaganda, a company run by David Fincher and Dominic Sena. Not long after, he began working on his first feature films: The Crow (1994), Dark City (1998), Garage Days (2002), I, Robot (2004), Knowing (2009). His next project is called Gods of Egypt, a film co-produced by Summit Entertainement, Lionsgate, and Mystery Clock, starring Gerard Butler and Nikolaj Coster-Waldau. What do you call a Scotsman and a Dane in Ancient Egypt? Well, a feast for the senses, if the trailers and stunning posters are anything to go by. In this special interview, Alex Proyas, a modern-day master of visual wizardry, took time out from his schedule to talk film, posters, and multiculturalism. Cultural melting pot As any good chef knows, combining flavours is a good thing, but you have to get the balance right. In the 60s, the Christian community in Alexandria was primarily made up of long-integrated Greek families. The region was a cultural and religious tinderbox waiting for the merest spark, with the new Arab Republics just waiting for an opportunity to get back at their former colonial oppressors. This situation led to friction between Arabs and Israelis, mass nationalisation, and Prime Minister Gamal Abdel Nasser's well-known pan-Arabist policies. While the progressive Nasser openly opposed the Muslim Brotherhood, this was not enough to stop many Greek Egyptians from fleeing the country. Among those who left were the Proyas family, who decided to move to Australia. So what would have happened to Alex if things had turned out differently? Let's not forget that Egypt is a country of cinema and music in its own right:

"Well I probably would not speak English. My family are Greek Egyptian, but they go back hundreds of years in Egypt. The reason the Greek-Egyptians left is their lives in Egypt were made very difficult by the regime at the time. A very sad situation after being so much a part of that culture for so long. Having said that I have a great affinity for the ancient mythologies of Egypt – that's why I made this movie".

In Sydney, on the other side of the world, Alex lost himself in the world of cinema. Watching Lawrence of Arabia was enough to get him hooked. Perhaps the desert, Omar Sharif, and the warm southern wind were enough to remind him of his Egyptian ancestors. His first feature-length film (Spirits of the Air, Gremlins of the Clouds, 1989) appeared to be very much in the same vein as other big-name Australian producers of the period, such as Russel Mulcahy and George Miller, who had a penchant for armageddon-type stories set in the outback. The power of these films lies in the music-video style blend of sound and image work:

"We Aussie film-makers like shooting in the desert – there is so much of it in Australia. Maybe that's where you see a connection ? Other than that not really sure I agree with you that there is much similarity between all those movies. SPIRITS was mainly unfluenced by the American western or more specifically Serio Leone's westerns".This love of striking images would stay with Alex and have a significant effect on his career.

A cult of images

Alex went on to work for the likes of Sting, INXS, Mike Oldfield, Nissan, Nike, and Adidas. His reputation as a master of visuals and his love of dark special effects became his trademarks. In 1994, he signed up to work on an 8-minute short film entitled Book of Dreams: "Welcome to Crateland". Not long after, he was approached by producer Ed Pressman to adapt a comic book by the famously talented yet troubled Irish American artist James O'Barr. Left almost entirely to his own devices through his childhood, O'Barr used his art as an escape from the miserable reality of his own life. When his fiancée was knocked down and killed by a car, he decided to enlist in the army. Two years later, he returned home to seek revenge on the driver of the car, only to discover he had died of natural causes. It was at that point that he began work on the now world-famous comic strip The Crow. The dark, black and white style of the imagery, interspersed with influences from rock music, appealed to Proyas immediately:

"It was a kind of anti-comic. That appealed to me in regard to making the movie. At the time I made that film the only real comic book movies were Tim Burton's Batman. I saw the Crow as being the antithesis of those films, and an opportunity to make something original in that genre".

The film adaptation suffered its own gruesome twist when Brandon Lee, son of the late Bruce Lee, was killed by a live round from a gun which was supposed to have been loaded with blank rounds. For O'Barr, this was a sign that the film was cursed, and he decided to donate all royalties earned to children's charities. He now lives a simple life with his new partner on the outskirts of Detroit. The film itself turned out to be a huge success across the board, grossing large sums of money and enjoying almost unanimous approval by critics and fellow film-makers alike. With its desaturated tints and faded colours, it remained true to the visual aspect of the original comic book, while the numerous tracking shots which followed the crow from rooftop to rooftop remain ingrained in fans' memories. Dark City provided Proyas with the opportunity to hone his skills in the production of action and drama films while working on a steam punk-style visual masterpiece. So where did the inspiration come from for this film?

"Tarkovsky, Fritz Lang, Hitchcock, Sergio Leone, Kubrick, Bunuel – the surrealists generally (I will make a film about them one day), Moebius, the 'Golden Age' science fiction authors, Clarke, Bradbury, Asimov, many many others..."

Employing a star-studded cast, Proyas pushed the limits of the genre. The city transformed under the gaze of the spectator. The combination of retro-modern imagery, music, and violent light contrasts makes the film both intimate and ambitious. You know you are dealing with a great director when you feel like you are stepping into their universe right from the get-go.

Actors and posters

Proyas is a passionate about his actors as he is about his posters. The poster is a window into what is in store, while actors are the people who bring the film to life. Alex is as much at ease working with Will Smith as he is with Rufus Sewell:

"Every actor is completely different. I do prefer working with actors who are collaborative in terms of story telling and can maintain an overview of the larger canvas. Though I do respect an actor working hard to make their character the best they can be. Posters should try and capture the 'experience' of the movie. I do not want to see a famous actor's head for its own sake – if they are famous everyone knows what they look like anyway. Show the mood or the emotion I will experience when I watch the movie".

The poster also reflects the personality of the director. When you see a poster, you know at a glance whether you are dealing with a veteran film-maker or merely a rookie. Proyas says he can "hardly ever" get the poster he wants due to restrictions imposed by distributors. On the rare occasions when this is possible, it is just as special as when a film fan gets their hands on the coveted director's cut. When it comes to posters, Alex knows what he's talking about. An avid collector of pieces from the 20s, 30s, and 40s, he is particularly interested in classic films, made in a period when artists played a key role in promoting new films. And what about his own films? On the French DVD release of Dark City, for example, a number of different versions of the poster are provided:

"That's really hard to answer. Maybe the original METROPOLIS poster. I collect old movie posters – generally for films made in the 20's 30's 40's – I just like the style, the fact they were painted and not photographic makes them works of art (not that photography cannot be art, but the modern approach of using photos of movie stars is just not appealing to me). With older posyets, often the quality of the movie they are promoting does not matter, the poster and the style of the artist, speaks for itself. I love the tall French poster which was done for the French release – and appeared around Paris at the time – still my favourite poster for any of my movies".

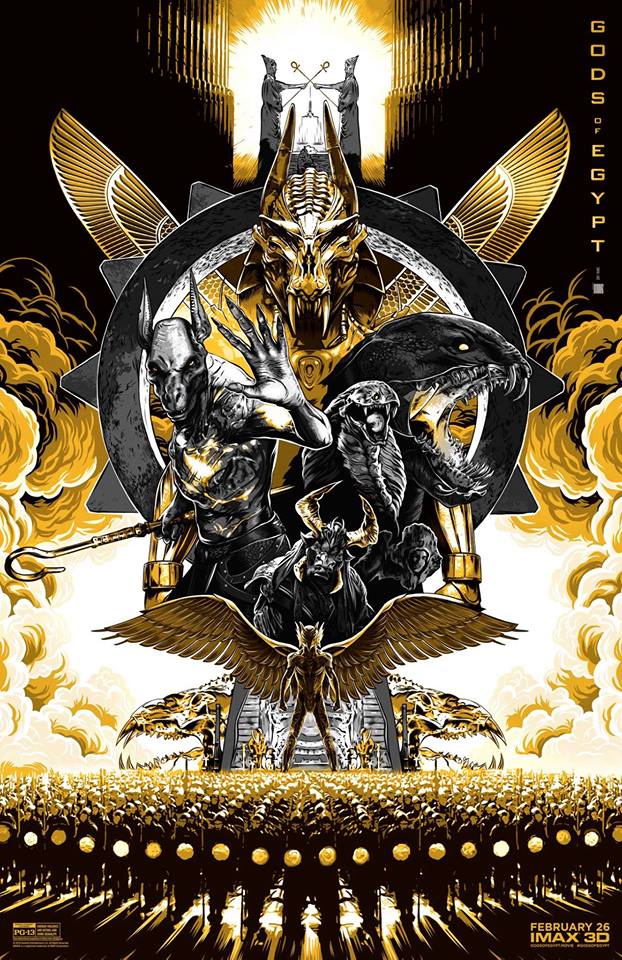

Alex Proyas' appetite for stunning imagery combined with striking story-telling is evident in many of his other films. I, Robot and Knowing are good examples, while Garage Days also shows glimpses of Proyas' particular flare in this domain. He is one of the few directors with a wide enough repertoire to encompass big-budget projects, Asimov, music, armageddon, and even working with children. But one question remains: who is behind the posters for Alex's films? "Marketing departments and distributors. Sometimes they are outsourced – one of my favourite posters for my movies lately is the IMAX one for Gods of Egypt". This is not surprising, given their independent style, despite being produced for a major Hollywood production company. They are very reminiscent of the style pioneered by Mondo Graphics, the ultra-creative company popular with film poster aficionados. There is a greater focus on the ambiance of the film rather than the cast. In this poster, we can see all the well-honed elements of a Proyas film: ambitious artwork, an insight into the narrative, and the ever-present special effects. One final question, if posters are so important, has the great Proyas himself ever been to see a film purely on the basis of its poster? "No. That is a bit like judging the book by its cover. But a good poster certainly makes me more excited to see a movie", us too! But in Imax preferably!

© Lionsgate

© Lionsgate